Normalization with Sudan, and who will pay the price?

Dr. Shani Bar-Tuvia | 30.08.2020 | Photo: Unsplash

A few days after the declaration of normalization of relations between Israel and the United Arab Emirates, the spokesman of the Sudanese Foreign Ministry announced talks on the normalization of relations between Sudan and Israel. After that statement the spokesman was fired. His dismissal seems to indicate the complexity of the Israeli issue through Sudanese eyes, a complexity described by Inbal Ben Yehuda in an article she published in the Ofek Project last February, after a meeting between Prime Minister Netanyahu and the chairman of Sudan’s Sovereignty Council. Despite that complexity, it appears that the establishment of relations between Sudan and Israel in the coming years is at the very least possible if not likely. What does that imply for the Sudanese refugees in Israel?

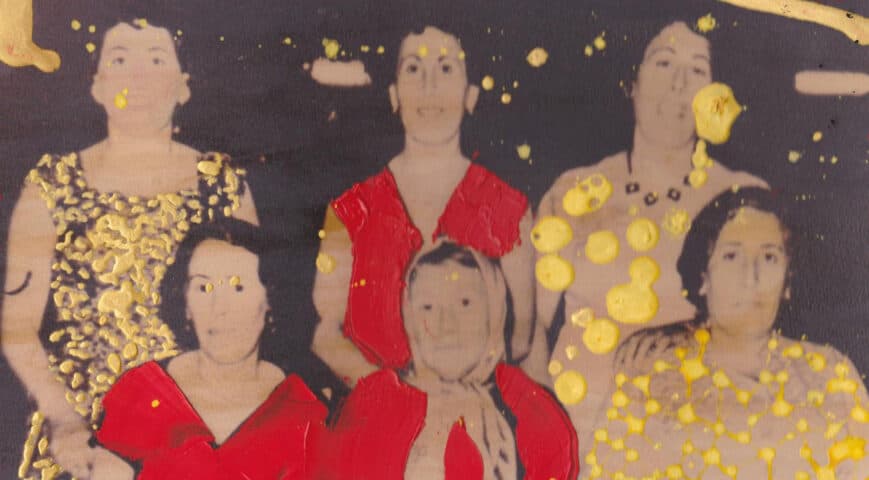

Reports in the Israeli media about the normalization of relations with Sudan in recent days, and government representatives interviewed on the subject, consistently made a connection between the normalization of relations and the return of the refugees (or, as the government representatives call them, “labor migrants” or “infiltrators”) to Sudan. On the other hand, there were those who hurried to explain why that would be neither legal, moral, or just in the near future. One reason is that the ethnic cleansing in Darfur and other areas is still going on, whereas Israel has for a decade avoided reviewing the asylum applications of Sudanese refugees. For more information on the status of asylum-seekers in Israel and Israel's policy towards them, see the book Where Levinsky Meets Asmara, published by the Van Leer Jerusalem Institute in 2015.

This local discussion, which will surely continue in the coming months or years, also exposes broader trends, beyond the question of the situation in Darfur or the relations between Israel and Sudan. These trends were recently discussed in the “Day After” events organized by the Van Leer Group Foundation, the Jerusalem Cinematheque, the Bernard van Leer Foundation, and the Van Leer Jerusalem Institute, about the day after the pandemic. In a conversation with him, the Chinese director and activist Ai Weiwei predicted that the waves of refugees of recent years would only increase, and claimed that was the price of globalization, which would start to be paid, and would continue to be paid in the future, by those who had heretofore benefited from it.

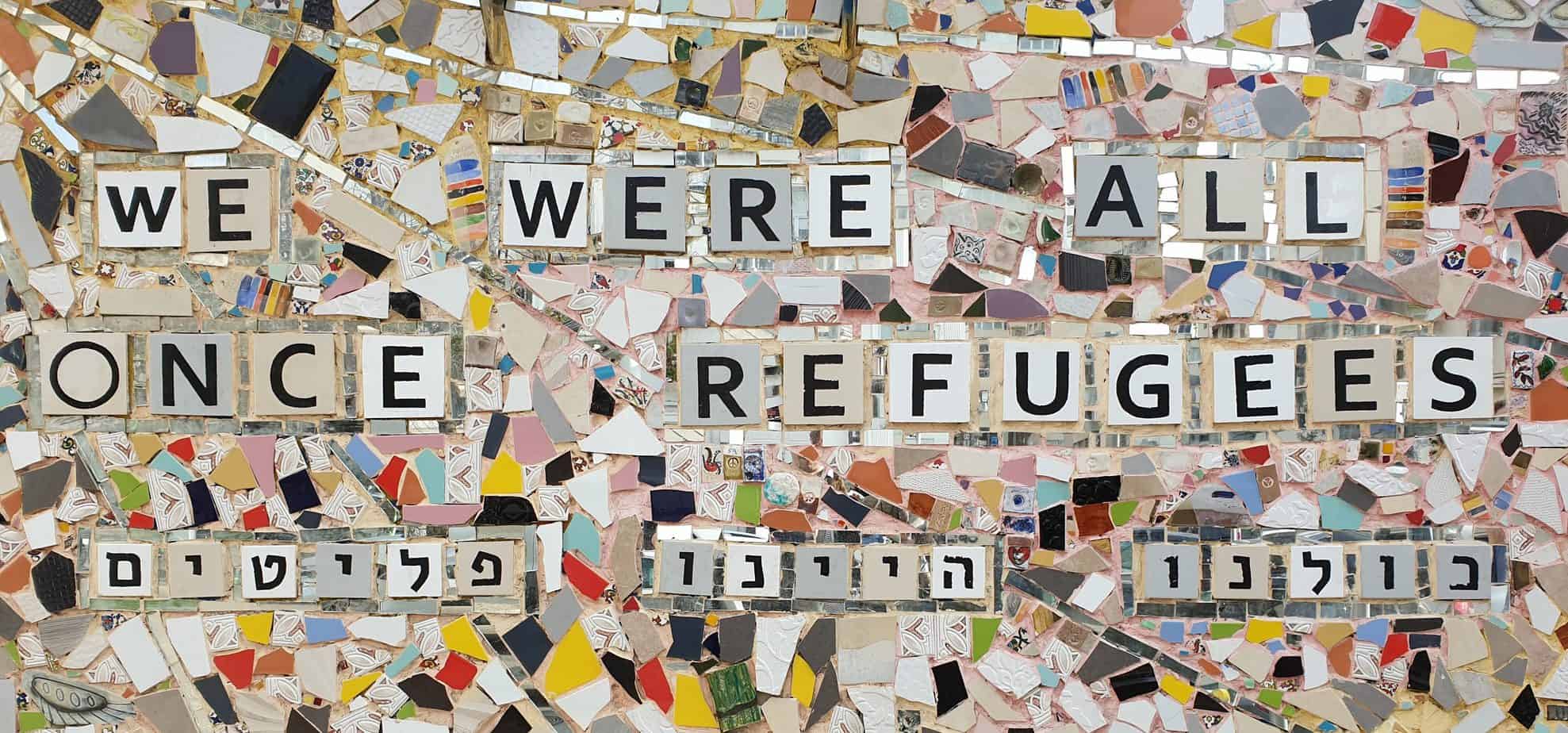

Whereas the first part of Ai Weiwei's argument looks like a reasonable prediction, and not many would dispute it, the second part seems more like a wish. Although the number of refugees in the world has been growing steadily in recent years, those who are presently paying the price are the refugees themselves and the poorest countries in the world who are hosting most of them. Israel, for instance, has managed in recent years to seal its borders hermetically to the entrance of refugees, and its governments have acted, as we have seen again in the last days, to make sure that even the small number of refugees on its soil would stay there only temporarily.

Israel is not alone. All of the countries that call themselves "Western" have over the past several decades enacted policies to prevent the entrance of refugees and other migrants into their territories. Although their "success" has usually been more limited than Israel's, in part due to Israel's unique geopolitical features, the bottom line is that fewer than 20% of the refugees in the world manage to reach the richest and most developed countries. If Israel's overtures towards Sudan succeed, it will be another opportunity to wonder: are the richest countries in the world really going to "pay the price?”