The Nation-State and Multinationalism as the Basis for Class Struggle

The 2022 elections exposed long-brewing social changes in Israeli society, some of which raise concern over the future of democracy in Israel. How can revisiting the history of multinational empires help us understand the situation in Israel? And can the nation-state, the product of the new political order established following World War I, help us understand how democratization might occur?

In three symposia in the series Where Do We Go Now? The Future of Israeli Society and Politics, leading intellectuals in their fields will discuss these and other questions. The topic of the first symposium will be The Lessons of the Elections: Expanding the Political Imagination. The second will be Jewish-Arab Partnership? After May 21 and November 22. The third will be Religion and Politics: Between Margins and Center.

The imperial framework as opportunity

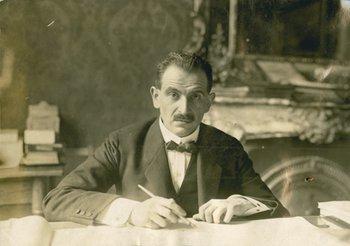

In 1907, just over a decade before the dissolution of the Habsburg Empire following World War I, Otto Bauer’s book The Question of Nationalities and Social Democracy (Die Nationalitätenfrage und die Sozialdemokratie) was published. A large part of the book was devoted to exploring class relations within the multinational state.

The centralistic-atomistic constitution, which turns the national struggle into an inevitable force, is intolerable from the point of view of the proletariat. The first demand for a proletarian constitutional policy in the multinational state is for a constitution that does not force the nations to participate in a struggle for power within the framework of the state. Every nation needs power, meaning the possibility to steer its course, realize its needs [...] The power of the nations to realize their cultural needs must be anchored in law so that the population is not forced to break down into national parties, so that conflict between national groups does not prevent the class struggle.

Bauer's words point both to the limits of the multinational imperial framework and the political horizons it opens. Bauer strongly criticized the Austrian liberal model, clearly expressed by the 1867 Austrian Constitution, which in his view underlay the material and class power relations between and within national groups. At the same time, Bauer viewed the multinational imperial framework, in which various nations coexist side by side cooperatively, as the political basis for realizing the class struggle. According to Bauer, the universalization of the class struggle will be made possible not by eradicating the national group but by the inverse process, in which the state provides the material conditions to all national groups within it and thus they become able to realize their collective existence without needing power struggles over hegemony in the state.

A new political order: The nation-state

Bauer wrote his work not long before the rise of the new political order after World War I. That new political order was manifested in the rise of nation-states in the territories of the Habsburg Empire and the creation of the mandates and expansion of the colonial regimes of Britain and France into areas of the Ottoman Empire. The war lowered the curtain on the multinational imperial frameworks and the horizons of political thought that they enabled. Ethnic groups began to think of themselves as being in a sort of anteroom, awaiting the arrival of the longed-for moment of achieving the coveted political structure of the nation-state. The new political order was perceived as a guarantee for the protection of certain national groups’ right of self-determination, and therefore some viewed it as an expression of democratization.

But the growth of the nation-states and the turning of the right of self-determination into the foundational principle of post-World War I political thought occurred in parallel to two additional processes. The first was denying that very right of self-determination to national groups subjected to European colonial rule—groups that had hoped that the rise in the status of that right would lead to their liberation from the yoke of foreign rule. The second process was the rise of the question of the minorities, because the political framework of the nation-state created a new foundation in which the balance of power in the state was linked to the relations between the national majority and the minority.

As Hannah Arendt argued, the arbitrary division of Eastern Europe into nation-states gave the keys of government to certain nations that became “state-nations,” whereas others from that very moment were assigned the status of “minorities.” That status directly constituted those groups as inferior to the majority groups, because even if they were seemingly part of a particular political framework, they were perceived as a threat to the cohesion of that framework because they threatened the most salient characteristic of the new political order—the precedence of the nation over the state.

Colonization, the nation-state, and the constitution of the Palestinians as a “minority”

The formation of Zionist settlement in post-World War I Mandatory Palestine manifested the convergence of the two processes associated with the rise of the nation-states: the exclusion of the nations subjected to colonial rule from the right to self-determination and the creation of minorities. The Mandatory government recognized the Zionist movement and its right to national self-determination, whereas, as part of the British attempt to create conditions for the realization of the promises given to the Zionist movement in the Balfour declaration, it denied the Palestinians national representation as part of the Arab executive committee of the Arab-Palestinian Congress. These conditions later enabled—after the expulsion of some 770,000 Palestinians and the prevention of their return—the establishment of the “liberal settler state,” as Shira Robinson called it.

The survivors of the Palestinian Nakba, while being constituted as a minority, were given limited civil rights, which were required by virtue of the international legitimacy given to the new Jewish nation-state. That status also expressed the duality that characterized the post-World War I global political order: On the one hand, the Palestinian citizens belonged to the State of Israel, but on the other hand they were perceived as an enemy and a fifth column threatening the state. That status was the basis for the various configurations of oppression directed at the Palestinian citizens of the State of Israel and its subjects (those who were not given civil status) throughout the years. The new threat to their democratic rights embodied in the results of the latest elections is actually an expression of additional power struggles within the Jewish settler society (as part of the ethnic and class power relations that characterize it), and its foundations are rooted in that constitutive moment of the emergence of the State of Israel as a nation-state and the state of all of its settlers rather than of all of its citizens.

Is it possible in Israel today, deep within the political order of the nation-state established following World War I—an order that absolutely negated the multinational imperial frameworks—for Bauer’s analysis to serve as a relevant basis for discussion? How can imperial memory contribute to the critical analysis of the prevailing order? According to Bauer, the prerequisite for democratization is the separation of nationality and state, to be accomplished not by neutralizing the state but by anchoring its support for all the national groups within it. That process, along with decolonization, which means stopping the settlement process, compensating its victims, and returning its refugees, is the necessary basis for any attempted democratization in the Israel-Palestine space and the basis for a complete transformation of the class power relations within it.